And maybe expand the topic a bit by profiling a couple of rocketeers I know and know of who are doing interesting scratch-built things. Blake's boost gliders and helicopter recovery rockets come to mind. I know for a fact he's doing things that haven't been covered in the modest pool of literature that's out there.

Rocket geeks love to argue about what glues are best for this task or that one. Yellow carpenter's glue, for instance, bonds at the molecular level on wood and paper, and makes an incredibly strong fin to body joint if done properly. While this is true, it is often said as if it's a reason to not use epoxy.

Epoxy has it's fans, and I guess I'm one of them. I've been experimenting some with working fiberglass into my construction palette, and have successfully used modest amounts of fiberglass tape on Stubby and the booster for Kandy Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby.

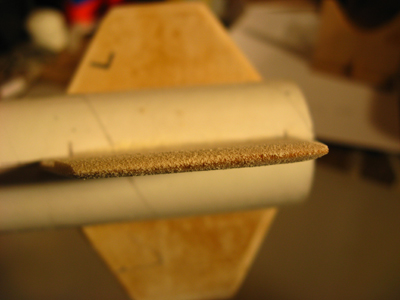

But I also like to use epoxy as a wood sealer on fins. I think it ads strength, and I know it keeps them from soaking up a bunch of paint. And on a balsa nose cone, it keeps the grain of the wood from raising up with each coat of paint.

On this guy, I got carried away sanding the resin finish for smoothness and sanded down to bare wood near the tips. I'm debating whether I'll come back after the fillets are set and apply finishing resin to the fins and do another sanding.

Don't be stupid if you use epoxy, by the way. When I sand this stuff, I wear a mask to avoid breathing the dust. And when you're handling the resin, wear gloves. I didn't the first couple of times I worked with the stuff, and started wearing gloves mainly because the honey-tar consistency of the stuff is unpleasant on the skin and was hard to scrub off. This was before I knew alcohol will clean epoxy up extremely effectively before it cures. But by the time I knew how to get it off easily, I also knew the shit is 'toxic by absorption.'

This is not Dev-Con's fault. Their package states this in bold type on the front of the package.

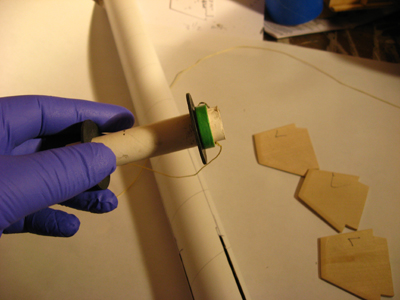

Anyway, nitrile gloves are ridiculously cheap and as far as I can tell entirely adequate for the task. I've seen pictures on John Coker's site (and other ones) showing heavier gloves, but for now I think I'm good with disposables. I'll buy the heavy gloves and the big respirator when I start sanding fiberglassed sono tubes on a lathe.

For my proposed project to break the sound barrier this year, I expect I'll glass the entire airframe and fin can. As you approach the speed of sound, there's all kinds of vibration and stress. So these rockets are, in part, practice at building techniques. I also like building them to bounce because of the inevitable failure of parachutes, or to make them specifically suited to streamer recovery.

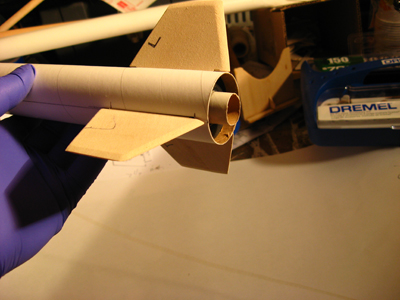

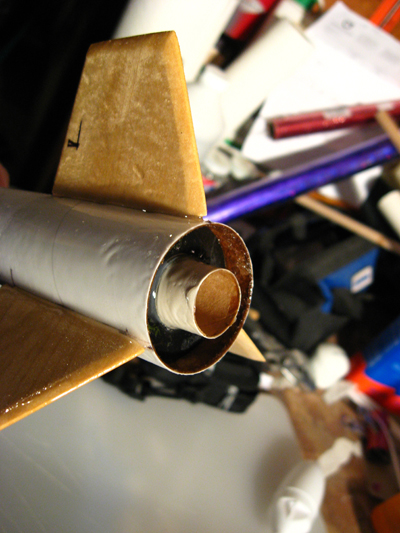

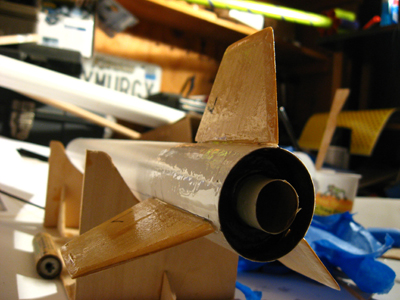

I showed the other night how I built the fins through-the-wall on this guy. Mounting fin tabs to the motor tube and then putting epoxy fillets at the joint with the fin and body tube is much stronger than a surface mounted fin. It's more work: the fin shapes are awkward to cut out with the tab, and slotting the body tubes is a little time consuming and needs to be pretty precise.

Test fitting everything is also important working with resins. When they set up, they're set up for good. The time to discover you need to sand another millimeter off here and cut that slot another hair's breadth wider is not while you've got the pot life ticker going. The Dev-Con I've used quite a bit claims a 30 minute pot life, but in reality, it's getting stiff after twenty minutes.

Another thing that messed me up the first few times was getting something to stay put while the epoxy is still fluid. On this rocket, for instance, I used white glue to pre-glue the centering rings to the motor mount, and secure the thrust ring. After that was dry, I coated it up with epoxy, brushed resin in the body tube and slid the motor tube in place.

I slathered plenty of epoxy on the motor tube between the centering rings because most of the epoxy on the fin tab gets scraped off by the edges of the fin slot. I brushed the epoxy out onto the fins before realizing that scraping action built a perfect fillet at the fin/body joint. Since I couldn't un-ring the bell, I ended up doing the fillets as a separate step.

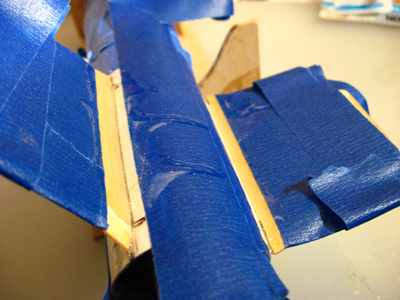

You'll notice in the photos, too, that I mask extensively. The thing about resinous substances, they're hard to get rid of when they go where you don't want them. Easier to not get them there in the first place. Likewise, I used a spent motor to keep epoxy out of the motor mount itself while brushing it liberally on the outside of the motor tube for added rigidity.

The other trick I photographed for this post is aligning the launch lugs. In lazy moments, I've used a single long launch lug, and that'd probably be fine for a rocket no bigger than this one (this isn't truly one of my usual clydesdales, only 18" long and only a BT-60 tube).

But two little lugs is more stable than one big one. I wanted to epoxy them to the body,but epoxy sets slowly. So as a first step, I used CA glue and baking soda (which creates an exothermic reaction causing the glue to set very quickly). Inserting the launch rod through the lugs and taping it in position on the body helps get the two lugs lined up accurately, though it's careful work not supergluing the launch rod to the rocket (voice of experience here).

I apologize if this post is long and rambling even by my standards. I might come back and edit it in a day or two.

No comments:

Post a Comment